I honestly debated about whether or not to write a blog post for Thanksgiving. Obviously, the part of my brain that told me to do it won out. So, here is today's post. For today, I thought I would do something a little different. Instead of focusing on Gaines' work or how he relates to other authors, I have chosen to focus on William Apess and his response to Daniel Webster's A Discourse, Delivered at Plymouth, December 22, 1820. (December 22 commemorated the arrival of the Pilgrims at Plymouth.) In his Discourse, Webster honors the Pilgrims and their arrival at Plymouth and even go as far as to say that they "impress[ed] this shore with the first footsteps of civilized man!" (6). The key word here, of course, is "civilized." Later, Webster intones,

Poetry has fancied nothing, in the wanderings of heroes, so distinct and characteristic. Here was man, indeed, unprotected and unprovided for, on the shore of a rude and fearful wilderness; but it was politic, intelligent and educated man. Everything was civilized but the physical world. Institutions containing in substance all that ages had done for human government were established in a forest. Cultivated mind was to set on uncultivated nature; and, more than all, a government, and a country, were to commence with the very first foundations laid under the divine light of the [C]hristian religion. (42)According to Webster, the Pilgrims "cultivated" the previous "uncultivated" land. This included, of course, cultivating the Native Americans of that land as well. Speaking during the era of Manifest Destiny, Webster notes that eventually the Pilgrims, and other settlers, moved further inland from the coast to cultivate the "savage" land: "Two thousand miles, westward from the rock where their fathers landed, may now be found the sons of the Pilgrims; cultivating smiling fields, rearing towns and villages" (46).

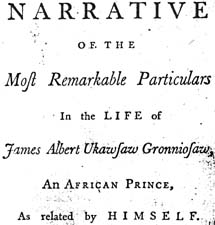

What Webster doesn't note is the people that the Pilgrims displaced and the "cultivation" they enacted upon those people and their communities. William Apess, a Pequot and Methodist minister, strove to counter Webster's view, and the dominant public view, of the Pilgrims as "civilized" cultivators and Native Americans as "savagely" uncultivated. In his Eulogy on King Philip (1836), Apess counters Webster, and others, by claiming that what they, and their forefathers, did in the name of Christianity did not represent what he knows about God. In effect, Apess takes the language of the master's house and uses it to dismantle the structure. Apess partly writes,

Throughout the Eulogy, Apess uses Christian rhetoric to counter the atrocities that the Pilgrims and other perpetrated upon King Philp's people and other Native Americans. Ultimately, Apess calls on people to stop celebrating December 22nd because of its actual connotations in regards to the displacement and murder of the people who inhabited this land before "the first footsteps of civilized man" appeared.But some of the New England writers say, that living babes were found at the breast of their dead mothers. What an awful sight! and to think too, that diseases were carried among them on purpose to destroy them. Let the children of the pilgrims blush, while the son of the forest drops a tear, and groans over the fate of his murdered and departed fathers. He would say to the sons of the pilgrims, (as Job said about his birthday,) let the day be dark, the 22d of December, 1622 let it be forgotten in your celebration, in your speeches, and by the burying of the Rock that your fathers first put their foot upon. For be it remembered, although the gospel is said to be glad tidings to all people, yet we poor Indians never have found those who brought it as messengers of mercy, but contrawise. We say, therefore, let every man of color wrap himself in mourning, for the 22d of December and the 4th of July are days of mourning and not of joy. Let them rather fast and pray to the great Spirit, the Indian's God, who deals out mercy to his red children, and not destruction. (14-15)

While Gaines did not live and write during the time of Daniel Webster and William Apess, he still echoes them, at least in regards to so called "civilized" man taking the "savage" land and taming it. During Ned's speech by the river in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, Ned comments that "America is for red, white, and black men"; however, Ned falls into the trap of diminishing the Native Americans' role in the cultivation of the land (115). He continues by saying, "The red man roamed all over this land long before we got here. The black man cultivated this land from ocean to ocean with his back. The white man brought tools and guns" (115). Here, the African Americans, as slaves, cultivated the land under the white man's oppression. In a way, the history that Ned presents mirrors Webster more than Apess.

Further in the novel, when Miss Jane talks about the oak tree, she talks about the levees being built to "contain" the Mississippi River. She begins by talking about how Native Americans, once they caught a fish, ate it and threw the bones back in the river so it could become another fish. When the white man arrived, he told the Native Americans that bones could not become fish again. They did not believe him, so the white man "conquered" them and killed them. After this, he "tried to conquer the same river that they had believed in, and that's when the trouble really started" (155). The levees, of course, failed. The white man could not conquer the river and "civilize" it to adhere to his plans.

Much, much more could be said about the topic of Webster and Apess in the 1830s and even about Gaines' representations of Native Americans. However, I think I should leave it here at this point. As usual, if you have any comments, leave them below.

Apess, William. Eulogy on King Philip. Boston: William Apess, 1837. Print.

Gaines, Ernest J. The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. New York: Bantam, 1972. Print.

Webster, Daniel. A Discourse Delivered at Plymouth, December 22, 1820. In commemoration of the First Settlement of New-England. Boston: Wells and Lilly, 1825. Print.