Currently, I'm rereading James Baldwin's Go Tell it On the Mountain (1953), and while working on my paper for an upcoming conference, I noticed some things that I would like to talk about briefly here on the blog. I've written about Baldwin and the southern landscape on this blog before. Today, I want to expand upon that to a certain extent by looking at Florence and Deborah in Baldwin's first novel. Trudier Harris notes that fears of the South “whether

manifested in lynching or rape, had a direct impact upon black bodies” (13). For Florence and Deborah, the fear of rape is what drives them, one to leave the South, and the other to become subjected to the power of Gabriel Grimes.

Farah Jasmine Griffin, in "Who Set You Flowin'?: The African-American Migration Narrative, talks about Florence's decision to migrate North while only touching briefly on Deborah and her non-movement. Griffin notes that in order to better understand what caused individuals to migrate to the North, especially females, we need to pay attention to the non-economic motives. For Florence, this motive included the fear that she would be raped by her "master." At home, Florence's place within the family can be seen as nothing more than tenuous because she must give up her self for Gabriel's success. Gabriel becomes the one that their mother dotes on, pushing Florence to the side. The sexism she experiences at home only exacerbates what possibly awaits her at her job in the white man's house.

When she was twenty-six years old in 1900, Florence decided to leave for New York. As she worked as a "cook and serving-girl" in a white home, "her master proposed that she become his concubine" (emphasis added 75). At that moment. Florence chose to escape. She bought a train ticket for New York and left the very next day. One important aspect to note in the above quote is that Baldwin uses the term "master" for Florence's employer. This event occurred 35 years after the Civil War, but he still chooses that term here. Griffin astutely notes that "Baldwin uses this term to denote that the South from which Florence flees is the same South as that which enslaved her mother" (38). The only impetus for Florence escaping is the threat of sexual exploitation by her master, not the death of a family member by violence or monetary desires.

Florence's friend Deborah actually experiences sexual trauma at the hands of white southerners, but she does not leave as a result. At sixteen, Deborah "had been taken away into the fields the night before by many white men, where they did things to her to make her cry and bleed" (69). After Deborah's father confronts the whites, they beat him and left him for dead. From that moment on, no one in the community would touch Deborah because they viewed her as unclean and a harlot. These experiences caused Deborah to believe that all men were only after her for her body, nothing more. She turned to the Lord, and eventually, after Gabriel's conversion, she marries the supposed man of God. Their relationship involved Deborah praising Gabriel, Gabriel accepting the praise, and not much more. In essence, Gabriel begins to lord over her with his power that purportedly came from God. Unlike Florence, though, Deborah stays in the South with Gabriel, never attempting to escape.

Along with Florence and Deborah, another woman experiences sexual exploitation. Esther, the woman who works with Gabriel and has an affair with him while he is married to Deborah, chooses to flee the South after her encounter with Gabriel leaves her pregnant. While Florence's and Deborah's instances of sexual subjugation occurred at the hands of white men, Esther's happened at the hands of an African American. The congress between Esther and Gabriel is consensual; however, once Gabriel finds out that Esther is pregnant and that she wants to leave, his power begins to show. He tries to reason that she is not pregnant and that she is just being naive, but Esther stands firm and starts to batter Gabriel's pride. She tells him that he needs to give her money so she can leave, or she will go through town telling everyone about "the Lord's anointed" and his actions. Gabriel acquiesces, and he steals the money Deborah had saved and gives it to Esther.

What makes Esther interesting is the fact that like Florence and Deborah she encounters sexual subjugation. Unlike Florence and Deborah, though, she experiences it not at the hands of whites but at the hands of an African American man. Along with this aspect, the results of her encounter with Gabriel mirror what happens with Florence. Even though Florence does not physically get raped, the mere thought of it causes her to migrate. The consensual congress of Esther and Gabriel causes her to flee because of the resulting pregnancy.

I'm not sure what to entirely make of this right now, but it's something that I noticed. What are your thoughts on this? Share them below.

Baldwin, James. Go Tell it On the Mountain. New York: Dell, 1985.

Griffin, Farah Jasmine. "Who Set You Flowin'?: The African-American Migration Narrative. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. Print.

Welcome to the Ernest J. Gaines Center's blog. Here, you will find information relating to ongoing projects at the Ernest J. Gaines Center. Along with information about the Center, this blog will serve as a spot to elaborate on Gaines' work and his relation to American literature, Southern literature, African American literature, and world literature.

Tuesday, March 31, 2015

Thursday, March 26, 2015

"A Visitation of Spirits" and the Past

|

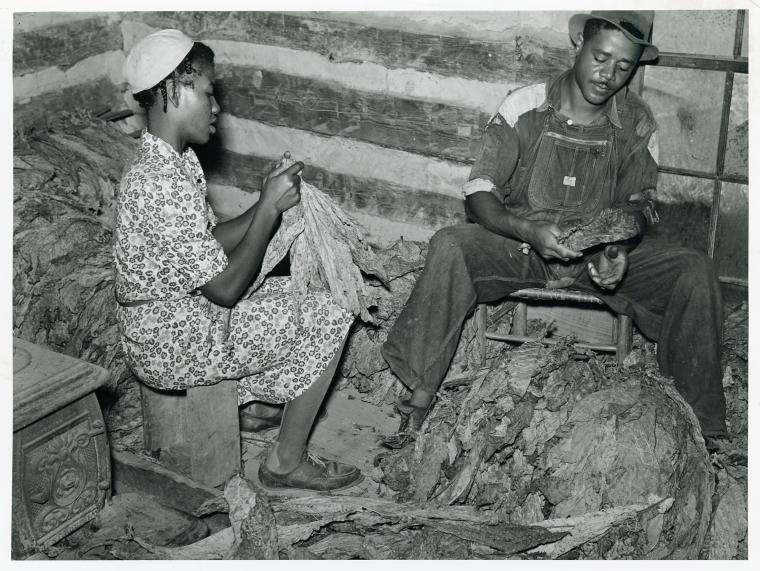

| African American sharecropper and wife grading tobacco in North Carolina (New York Public Library) |

"Requiem for Tobacco" begins nostalgically, almost like a myth that was once true but as of now no longer exists.

You remember, though perhaps you don't, that once upon a time men harvested tobacco by hand. There was a time when folk were bound together in a community, as one, and helped one person this day and that day another, and another the next, to see that everyone got his tobacco crop in the barn each week, and that it was fired and cured and taken to a packhouse to be graded and eventually sent to market. But this was once upon a time. (254)"Once upon a time," as Davis notes, carries with it a note of mythologizing the harvest. The phrase, in one form or another, appears twice in the paragraph above, once at the beginning and once at the end. Along with this phrase, there is also a focus on community. Looking to the past, the narrator points out that it "was a time when folk were bound together in community." Community plays a major role in Gaines's work, and in Kenan's novel, the community that "Requiem for Tobacco" recalls does not exist anymore. Instead, the community does not help one another out; in fact, it hinders the psychological growth of the presumed One, Horace.

After speaking about the planting, harvesting, and drying of the tobacco. Men like Edgar Harris and George Pickett would plant and harvest the tobacco then bring it to the barn where the women would tie the tobacco together. Underneath the tin ceiling, time would fade away, problems would be solved, and the older women would "impart good and practical wisdom to younger girls" (256). All of this though, happened in the past. Over time, the land, and who cultivated it, changed. The encroachment of modernity upon the rural North Carolina community recalls the continued approach of mechanized farming in Catherine Carmier and A Gathering of Old Men. Now, Edgar Harris lies in a grave somewhere and "George Pickett has leased his land and now drives a bus" (256). Pickett's land then became divided again, sold to someone who had a lot of land, "someone who is no one at all, but many in the name of one," a corporation like the one that harvests sugarcane in Attica Locke's The Cutting Season (256). Instead of hands doing the work, "the clacking metal and durable rubber of a harvester that needs no men, that picks the leaves, stores the leaves, slaps them into small bulk barns that looks like chicken coops that cure quicker, easier, cheaper" replaced the people in the fields (256-57). The increase in mechanized farming and corporations concerned more with profit margins than with people push the memories of Hiram Crum, Ada Mae Philips, Jess Stokes, Henry Perry, and Lena Wilson to the side, letting them drift in the wind like the dust kicked up by a laboring tractor.

"Requiem for Tobacco," and the novel, concludes with paragraph that laments the passing of time. Even though machines make farming "less torturous," they also erased the past. With the movement of modernity, the past becomes forgotten, only to be recalled when modernity causes us to feel more disoriented then ever from trying to keep up. That is when we turn to the rural, the pastoral, for an escape from the overwhelming onslaught. That should not be the only time. As the narrator concludes, "And it is good to remember that people were bound to" the process of growing tobacco "for too many forget" (257). This is what Gaines writes for. This is what Kenan's A Visitation of Spirits does. They cause us to remember, to look at the past and to recall how we made it to the present.

|

| Wood Plank Road in Fayettville, NC (1984) |

What other instances in Kenan's novel highlight the changing times? Are there other instances that remind you of Gaines or other Southern authors? If so, what are they?

Davis, Thadious M. Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, & Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Print.

Kenan, Randall. A Visitation of Spirits. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Print.

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

Randall Kenan's "A Visitation of Spirits"

On the surface, Randall Kenan's A Visitation of Spirits (1989) may not seem similar to works by Ernest J. Gaines, at least in regards to the writing style. Kenan's novel oscillates from narrative to narrative in a postmodernist stream-of-consciousness flow. Gaines, on the other hand, writes in a more straight forward narrative style that mirrors Hemingway, with the occasional stream-of-consciousness here and there. While styles do not necessarily link Gaines and Kenan, other similarities do arise here and there. What one sees when reading Gaines and Kenan in unison arises from the thematic similarities of two African American men from the South but born thirty years apart. Even though he was born in New York, Kenan grew up in North Carolina, and Chinquapin, NC, serves as the inspiration for Tims Creek, the community where Kenan sets his fiction. Along with the creation of specific space like Gaines's Bayonne and Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County, he allows for a sense of reality in his fiction, even though the novel is very speculative, filled with demons and other spirits that occupy the mind of Horace Cross.

While reading, there are certain aspects of A Visitation of Spirits that make me think of Gaines and Southern writers. For one, I think about community. Gaines's works center on community, as I have noted before. The community in the quarters, to a certain extent, serves as a space where the African American occupants do not come face-to-face with racism and oppression as they do when they go to town. Think about Gaines's "The Sky is Gray" here. James does not experience overt subjugation in the quarters; he experiences community. When he goes to Bayonne, he starts to come more overtly into contact with the systems that keep him oppressed. In Gaines's work, the community struggles with the legacy of slavery, but they all form a system that supports and works together. However, as Trudier Harris argues, "the legacies of slavery are somewhat in the background" of Kenan's novel, and "a sense of black family tradition has become so all-consuming that it is perhaps worse than slavery" (115). At the center of this "all-consuming" community is Horace Cross, "the Chosen Nigger" (13). Harris points out that Horace's being labeled "the One" that will serve as a leader for the community mirrors numerous characters in Gaines's works, most specifically Ned Douglass and Jimmy Aaron in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971).

While Ned and Jimmy both succeed in becoming "the one," Horace Cross cannot. He studies, maintains good grades, and works hard to become something extraordinary beyond the teachers, preachers, and lawyers that surround him. However, Horace is gay, and the patriarchal, heterosexual family lineage that values the conquering of "pussy" does not allow for a homosexual leader (55). Instead of being lifted up and groomed to be the leader of the people, the community diminishes Horace's worth and condemns him vociferously. In the church at night, Horace envisions the pastor condemning him from the pulpit and calling him calling him "unclean." Then, Horace starts to hear voices from the congregation, including his family. They say,

Wicked. Wicked.

Abomination.

Man lover!

Child molester!

Sissy!

Greyboy!

Old men, little girls, widows and workers, he saw no faces, knew no names, but the voices, the voices . . .

Unclean bastard!Through their name calling and other actions, the community that initially labels Horace as "the One" systematically tears him down, refusing to accept him as he is and leading him to his ultimate demise. In Kenan's novel, the downfall of "the One" does not come from the outside community, the white community that tries to maintain its rule over the African American community. Instead, the destruction occurs from the inside. This is not to say that the residual effects of slavery do not contribute to the people "othering" Horace. I would even argue that the labeling of Horace as "the Chosen Nigger" works to devalue his place as well. Instead of calling him "the chosen One," the epithet used completely reduces Horace to a person who will not become a savior for those around him but to someone who will go through life subjugated and beaten down by a system that continually strives to maintain control.

Be ashamed of yourself!

Filthy knob polisher! (86-87)

In the next post, I will talk about another similarity I see between Gaines and Kenan: the land. Both authors describe the land thoroughly, and its changing appearance. What similarities do you see between the two authors? Let me know in the comments below.

Harris, Trudier. The Scary Mason-Dixon Line: African American Writers and the South. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2009. Print.

Kenan, Randall. A Visitation of Spirits. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Print.

Thursday, March 19, 2015

New Items in the Collection and Marginalia

On Tuesday, I wrote about Sister Mary Ellen Doyle's involvement in the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965 and how they impacted her life and career. Recently, the center received items from Sister Doyle to add to the Ernest J. Gaines collection here at UL Lafayette. Today, I would like to take a moment to highlight some of the items and to discuss their importance to the collection. sister Doyle sent newspaper articles, scholarly journal articles, and reviews about Gaines and his work. Along with these items, she also donated correspondence between Gaines and herself, her collection of Gaines novels, and lectures that she delivered on Gaines at various occasions.

We just received the items a couple of days ago, so I have not had the chance to scour through in full yet. However, I did notice a couple of things that I would like to share with you today. For one, all of Sister Doyle's books contain detailed marginalia. What do I mean by this? On the first couple of pages, she briefly summarizes each chapter in the novel and then summarizes key points. Throughout the chapters, she makes notes and underlines important texts. Why she would care about her marginalia? I recall visiting an exhibition of books from Thomas Jefferson's library once. There, in each of the books that were on display, I could see his marginalia notes. He wrote in his books. He conversed with the books. We have to remember that books, even though they are inanimate objects and we read them, typically, in solitude, are not solitary experiences. When we read, we interact with the author. Marginalia allows for a conversation to occur, and it also provides a space for notes and ideas to be remembered. Perusing Jefferson's marginalia provides us with insight into Jefferson's mind and also into how he interacted with the text he was reading at the time. Jefferson's marginalia even allowed scholars to denote books that were sitting in a special collection in Washington University for 131 years as books that once belonged to Thomas Jefferson. For another article on why marginalia is important, see "Book Lovers Fear Dim Future for Notes in the Margin"; it discusses marginalia by Mark Twain in a book about how to turn a profit in publishing books.

Back to Sister Doyle's marginalia for a moment. One of the first things I did when I received the books was flip through the to see her copious notes. While doing this, I lighted upon a couple of pages and topics that I have written about in the blog. Low and behold, on the pages were Sister Doyle's notes. Sometimes they agreed with what I though, sometimes not. However, they always provided me with more insight not only to Gaines's writing but also to Sister Doyle as a scholar and writer herself. The images provide two examples of Sister Doyle's marginalia. The first is from Of Love and Dust. Here, she speaks about the symbolism of the dust in the novel, something I posted on recently. In the margin, Sister Doyle writes, "Dust like white lyncher, symbol of white power Marcus can't fight, also of lifeless, dry existence he must endure at Hebert's." Sister Doyle's notes here summarize, succinctly, the symbol of dust within the novel, and they also make me think about the line that she has underlined in the final paragraph: "That dust was white as snow, hot as fire." The comparison of the dust to "white" snow is unmistakable, and I think that Sister Doyle's insight here helps to make that abundantly clear.

Back to Sister Doyle's marginalia for a moment. One of the first things I did when I received the books was flip through the to see her copious notes. While doing this, I lighted upon a couple of pages and topics that I have written about in the blog. Low and behold, on the pages were Sister Doyle's notes. Sometimes they agreed with what I though, sometimes not. However, they always provided me with more insight not only to Gaines's writing but also to Sister Doyle as a scholar and writer herself. The images provide two examples of Sister Doyle's marginalia. The first is from Of Love and Dust. Here, she speaks about the symbolism of the dust in the novel, something I posted on recently. In the margin, Sister Doyle writes, "Dust like white lyncher, symbol of white power Marcus can't fight, also of lifeless, dry existence he must endure at Hebert's." Sister Doyle's notes here summarize, succinctly, the symbol of dust within the novel, and they also make me think about the line that she has underlined in the final paragraph: "That dust was white as snow, hot as fire." The comparison of the dust to "white" snow is unmistakable, and I think that Sister Doyle's insight here helps to make that abundantly clear.

I also opened A Lesson before Dying and looked at the very last page, curious to see what Sister Doyle would write on the final lines of the book. Here, Grant has just heard about Jefferson's execution, and Paul gives him Jefferson's diary. The novel ends with three simple words, "I was crying." Again, I have written about this before, so I was curious to see what her thoughts were on the final line. Specifically, her initial thoughts before she transferred them into a longer piece. In regards to the last line of the novel, she writes, "He [Grant] finally has his break-through. In beginning, he only made the children cry." Her notes here make me reexamine what I initially thought about Grant crying at the end of the novel. I do see it as a "break-through," but I did not necessarily relate his crying here to his actions earlier where he made the children in the school cry. The other note is about style and form as well as themes. She writes, "Poignancy of ending from its beauty and understatement. But clear implication that he will be a different sort of teacher now, with hope for his students." This simple note provides us with insight into Grant's transformation, but it also causes us to look at Gaines's style and form in the novel, and specifically how he uses it at the end.

I also opened A Lesson before Dying and looked at the very last page, curious to see what Sister Doyle would write on the final lines of the book. Here, Grant has just heard about Jefferson's execution, and Paul gives him Jefferson's diary. The novel ends with three simple words, "I was crying." Again, I have written about this before, so I was curious to see what her thoughts were on the final line. Specifically, her initial thoughts before she transferred them into a longer piece. In regards to the last line of the novel, she writes, "He [Grant] finally has his break-through. In beginning, he only made the children cry." Her notes here make me reexamine what I initially thought about Grant crying at the end of the novel. I do see it as a "break-through," but I did not necessarily relate his crying here to his actions earlier where he made the children in the school cry. The other note is about style and form as well as themes. She writes, "Poignancy of ending from its beauty and understatement. But clear implication that he will be a different sort of teacher now, with hope for his students." This simple note provides us with insight into Grant's transformation, but it also causes us to look at Gaines's style and form in the novel, and specifically how he uses it at the end.

With this post, I wanted to highlight the importance of writing in books. I write in books to remember thoughts and to converse with the author. I always tell my students to write in the margins, but most of them still don't. We view books as something sacred that should not be tampered with. That's not the case. What do you think about marginalia? Is it something that is important? Or, is it something we shouldn't care about at all?

We just received the items a couple of days ago, so I have not had the chance to scour through in full yet. However, I did notice a couple of things that I would like to share with you today. For one, all of Sister Doyle's books contain detailed marginalia. What do I mean by this? On the first couple of pages, she briefly summarizes each chapter in the novel and then summarizes key points. Throughout the chapters, she makes notes and underlines important texts. Why she would care about her marginalia? I recall visiting an exhibition of books from Thomas Jefferson's library once. There, in each of the books that were on display, I could see his marginalia notes. He wrote in his books. He conversed with the books. We have to remember that books, even though they are inanimate objects and we read them, typically, in solitude, are not solitary experiences. When we read, we interact with the author. Marginalia allows for a conversation to occur, and it also provides a space for notes and ideas to be remembered. Perusing Jefferson's marginalia provides us with insight into Jefferson's mind and also into how he interacted with the text he was reading at the time. Jefferson's marginalia even allowed scholars to denote books that were sitting in a special collection in Washington University for 131 years as books that once belonged to Thomas Jefferson. For another article on why marginalia is important, see "Book Lovers Fear Dim Future for Notes in the Margin"; it discusses marginalia by Mark Twain in a book about how to turn a profit in publishing books.

Back to Sister Doyle's marginalia for a moment. One of the first things I did when I received the books was flip through the to see her copious notes. While doing this, I lighted upon a couple of pages and topics that I have written about in the blog. Low and behold, on the pages were Sister Doyle's notes. Sometimes they agreed with what I though, sometimes not. However, they always provided me with more insight not only to Gaines's writing but also to Sister Doyle as a scholar and writer herself. The images provide two examples of Sister Doyle's marginalia. The first is from Of Love and Dust. Here, she speaks about the symbolism of the dust in the novel, something I posted on recently. In the margin, Sister Doyle writes, "Dust like white lyncher, symbol of white power Marcus can't fight, also of lifeless, dry existence he must endure at Hebert's." Sister Doyle's notes here summarize, succinctly, the symbol of dust within the novel, and they also make me think about the line that she has underlined in the final paragraph: "That dust was white as snow, hot as fire." The comparison of the dust to "white" snow is unmistakable, and I think that Sister Doyle's insight here helps to make that abundantly clear.

Back to Sister Doyle's marginalia for a moment. One of the first things I did when I received the books was flip through the to see her copious notes. While doing this, I lighted upon a couple of pages and topics that I have written about in the blog. Low and behold, on the pages were Sister Doyle's notes. Sometimes they agreed with what I though, sometimes not. However, they always provided me with more insight not only to Gaines's writing but also to Sister Doyle as a scholar and writer herself. The images provide two examples of Sister Doyle's marginalia. The first is from Of Love and Dust. Here, she speaks about the symbolism of the dust in the novel, something I posted on recently. In the margin, Sister Doyle writes, "Dust like white lyncher, symbol of white power Marcus can't fight, also of lifeless, dry existence he must endure at Hebert's." Sister Doyle's notes here summarize, succinctly, the symbol of dust within the novel, and they also make me think about the line that she has underlined in the final paragraph: "That dust was white as snow, hot as fire." The comparison of the dust to "white" snow is unmistakable, and I think that Sister Doyle's insight here helps to make that abundantly clear. I also opened A Lesson before Dying and looked at the very last page, curious to see what Sister Doyle would write on the final lines of the book. Here, Grant has just heard about Jefferson's execution, and Paul gives him Jefferson's diary. The novel ends with three simple words, "I was crying." Again, I have written about this before, so I was curious to see what her thoughts were on the final line. Specifically, her initial thoughts before she transferred them into a longer piece. In regards to the last line of the novel, she writes, "He [Grant] finally has his break-through. In beginning, he only made the children cry." Her notes here make me reexamine what I initially thought about Grant crying at the end of the novel. I do see it as a "break-through," but I did not necessarily relate his crying here to his actions earlier where he made the children in the school cry. The other note is about style and form as well as themes. She writes, "Poignancy of ending from its beauty and understatement. But clear implication that he will be a different sort of teacher now, with hope for his students." This simple note provides us with insight into Grant's transformation, but it also causes us to look at Gaines's style and form in the novel, and specifically how he uses it at the end.

I also opened A Lesson before Dying and looked at the very last page, curious to see what Sister Doyle would write on the final lines of the book. Here, Grant has just heard about Jefferson's execution, and Paul gives him Jefferson's diary. The novel ends with three simple words, "I was crying." Again, I have written about this before, so I was curious to see what her thoughts were on the final line. Specifically, her initial thoughts before she transferred them into a longer piece. In regards to the last line of the novel, she writes, "He [Grant] finally has his break-through. In beginning, he only made the children cry." Her notes here make me reexamine what I initially thought about Grant crying at the end of the novel. I do see it as a "break-through," but I did not necessarily relate his crying here to his actions earlier where he made the children in the school cry. The other note is about style and form as well as themes. She writes, "Poignancy of ending from its beauty and understatement. But clear implication that he will be a different sort of teacher now, with hope for his students." This simple note provides us with insight into Grant's transformation, but it also causes us to look at Gaines's style and form in the novel, and specifically how he uses it at the end.With this post, I wanted to highlight the importance of writing in books. I write in books to remember thoughts and to converse with the author. I always tell my students to write in the margins, but most of them still don't. We view books as something sacred that should not be tampered with. That's not the case. What do you think about marginalia? Is it something that is important? Or, is it something we shouldn't care about at all?

Tuesday, March 17, 2015

Sister Mary Ellen Doyle and the Selma-Montgomery Marches in 1965

|

| Sister Mary Ellen Doyle in Montgomery in 1965 |

Thinking about her life growing up in the Chicago suburbs, she recalled that the only African Americans she saw were workers: maids, gardeners, and live-in servants. None of them resided in her River Forest neighborhood. Pre-Brown V. Board of Education, when she began teaching Owensboro, KY, Sister Doyle began to notice the injustices of segregation more. She encountered African American children who had difficulty reading, partly because they could not get a library card to go to the public library. For Christmas, Sister Doyle asked her parents for money so she could buy books for the children. Even after the monumental decision in 1954 to desegregate public schools, she still noticed that parents did not want their children mixing with African American students.

Almost eleven years later, Sister Doyle took part in the Civil Rights marches in Montgomery, AL. There, Doyle experienced racism first hand. As she marched in response to the subjugation and oppression that white Southerners perpetuated on the African American community, Sister Doyle recalls encountering crowds as she drove to the airport with others who made the trip to Alabama with her. She was scared for her life, especially since the KKK recently murdered Viola Liuzzo a white mother of five while she drove marchers to the airport. On her way out of Alabama, she recalls seeing headlines on papers negatively portraying the events, calling the marchers hostile and speaking of those like Sister Doyle as invaders. However, in places like Chicago, the headlines read more favorably.

The events in Alabama shaped Sister Doyle's life, and they inspired her to use her teaching skills to enact social change. In the 1960s and 1970s, she began incorporating African American literature into her American literature courses. When she first started to write about Ernest Gaines, Sister Doyle recalls, "I think [Gaines] was a little flabbergasted at first. . . . 'Where did this white nun come from with all this interest in my writing?'" (A9) For Sister Doyle, her activism, and her involvement in the Selma to Montgomery marches shaped her life. It opened up her eyes to the racism that existed, and it also provided her with insight into the multicultural nation that America is and to what it could be. Her career worked towards fulfilling this vision of a multicultural society where everyone exists together.

I would just like to leave with a quote from Sister Doyle's Voices from the Quarters. Here, she is speaking about A Gathering of Old Men, and she links Gaines and King together in their ideas of finding ones voice and standing up against oppression. She writes,

The victory of Gaines's old men, like that of their race, occurs first in a change within their own minds, a new way of seeing themselves and their people, as well as the white race in all its historic power, benevolent and brutal. Transformed vision, as King and Gaines imply, releases the voice, enables speech and action, a 'stand' for justice. All this makes real social change possible if both races can see and hear themselves and each other as individuals and as a community. (176)For Sister Doyle, the history that I read about in books like The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman or in history books did not occur in the distant past. In fact, some of the events occurred during her lifetime, and Gaines's, and she recalls them as catalysts for her life's path. That is why speaking and listening to people like her and Ernest Gaines is important. They are individuals who not only researched history and literature, they lived it, just as we are living it now.

The article in the Kentucky Standard about Sister Doyle can be found on their website. The photos her are credited to Kacie Goode on the Kentucky Standard's site.

Doyle, Mary Ellen. Voices from the Quarters: The Fiction of Ernest J. Gaines. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002. Print.

Goode, Kacie. "Putting principles to practice: SCN shares about Civil Rights Movement, involvement in Selma-Montgomery march." Kentucky Standard [Bardstown] 15 Feb. 2015: A1, A9. Print.

Thursday, March 12, 2015

The Ernest J. Gaines Center's Library Guide

Recently, the Ernest J. Gaines Center has neared completion on its Library Guide (libguide). The libguide is meant to serve as an instructional tool to assist teachers, students, and scholars when they read the works of Ernest J. Gaines. On the libguide, visitors will find information on each of Ernest J. Gaines's books, including a specific page for his most anthologized story "The Sky is Gray." Along with these pages, the libguide includes a bibliography of Gaines's works and recent scholarship and a page that highlights a few items from the collection. At this moment, we have not completed the page for Catherine Carmier. We should have the information up for Gaines's first novel soon. Even though that page is not up yet, the guide provides visitors with copious amounts of information regarding Gaines's works and questions that one might ask while reading the texts. Used in conjunction with the blog, the libguide can be a useful tool either when planning a class or when research for a paper. To the left, you will see an image on the libguide page for Of Love and Dust. Click on it, and it will take you that page on the guide.

Each page on the libguide provides the same information for easy navigation.

Each page on the libguide provides the same information for easy navigation.

- The left hand column always contains items from the collection. These may be book covers, papers, correspondence, drafts, editor's comments, etc.

- The right hand column contains five sections.

- Background information typically provides interviews with Gaines or links to other websites that will provide context for the work being discussed. This section is typically followed by some for of media (either video or audio).

- The questions to consider section provides visitors with about six questions to consider when reading the text. The questions may refer the visitor to the items on the left, articles, or other information that may be pertinent.

- The possible activities sections is meant to help teachers think about possible links between Gaines's works and other authors. Here, a visitor will find six possible activities related to the novel being discussed. The activities range from further research on a topic rewriting a part of the book. Some of the activities as students to look at the archival materials on the left of the page as well.

- The next section focuses on Gaines and writing. Here, one finds a quote by Gaines either on writing in general or on writing the text being examined on the libguide page.

- The final section consists of scholarly articles about the work and typically a piece or two by Gaines himself. Sometimes the Gaines piece comes from the archive, and sometimes it has been published elsewhere.

We hope that the libguide will be useful to you as you teach or research Gaines and his work. What would you like to see on the libguide? Are they any specific items that would help you when either teaching or conducting research? Let us know in the comments below.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

The Whitney Plantation and Remembering Slavery

Last Tuesday, I attended a lecture by Dr. Ibrahima Seck, Director of Research at the Whitney Plantation in Wallace, LA. The plantation is the first of its kind in the United States because instead of focusing on the masters of the property and the architecture and grandeur of the "big house" it focuses on the lives of those who made the masters prosperous and the big house even possible, the chattel slaves who worked the land and sustained the economy of the plantation. I've written about this subject on this blog before, briefly, when talking about Attica Locke's The Cutting Season, a novel which takes place on a plantation that now hosts weddings, tours, and events causing it to become a place where the South gets remembered not for those who built it with their hands but for those who benefited off of that work.

Whitney Plantation's focus provides a unique opportunity for its visitors because it shows them the horrors of the peculiar institution. Visitors listen to the voices of former slaves, gathered in the 1930s by workers for the Federal Writers Project. All of these individuals, of course, were only children during slavery, so they recall bondage through the eyes of a child. Because of this, the plantation contains numerous sculptures by Woodrow Nash, some of which you can see in the video above and the picture below. They are all children, not adults, because the voices you hear as you walk through the grounds are those of people who were children before 1865. Along with the sculptures, the plantation contains memorials to the thousands of slaves who lived in Louisiana. One memorial, The Field of Angels, is dedicated to the 2,200 slave children in Louisiana who died before their third birthday. Unlike the monuments like the Wall of Honor (dedicated to slaves on Whitney Plantation) and the Allées Gwendolyn Midlo Hall (dedicated to the 107,000 enslaved people in Louisiana appear in the "Louisiana Slave Database"), the memorials in the Field of Angels are low for children to read the names. When hearing about this section, and the fact that some of the children did not have names or that their mother's name did not appear in the records, I could not help but recall Toni Morrison's Beloved , which was inspired by the case of Margaret Garner, a slave who escaped and upon being surrounded by slave catchers killed her two year old daughter by slitting the girl's throat with a butcher knife. I wondered, as Dr. Seck spoke, how many of the children on that wall experienced something similar or if they all died of diseases, neglect, and other maladies of the day.

Another thing that I started to ponder during Dr. Seck's talk was the actual land and the "rules" that allowed the plantation owner's brother, Antoine Haydel, to rape a slave named Anna who conceived a baby named Victor. Information about Victor and his lineage can be found on the Wall of Honor page. Upon hearing the story of Antoine and Anna, I immediately started to think of Tee Bob and Mary Agnes in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman and about Bonbon and Pauline in Of Love and Dust. I also began to ponder the land. Last spring, I took a class to New Orleans for a literary tour. I've been to New Orleans numerous times, and whenever I am there, or in another city, I think about who may have walked the streets before me. In New Orleans, that list would be very large. In fact, during the tour, the guide pointed out two buildings, both of which I had visited earlier that same day, where literary salons with Sherwood Anderson, Tennessee Williams, and others took place. I never would have guessed it. When I walk the land on River Lake Plantation, the thoughts about who walked here before me become stronger. The numbers decrease because of the rural setting, and I know that those who populated the land were either the perpetrators or recipients of oppression. I know that the people that Ernest Gaines writes about lived there, and are buried there. The connection is stronger. John Callahan has mentioned that on that land you can feel the spirit of the people. They are there. Even though I haven't been to Whitney Plantation yet, I imagine it is the same feeling. I know what occurred there, Super Bowls didn't, conferences didn't, huge Mardi Gras parades didn't, music festivals didn't. What occurred there is something we still live with, and something we must remember. I think Dr. Seck summed it best when he said the purpose of the plantation is "not to have anyone feel guilty but to teach people about the legacy of slavery." It is something that needs to be taught because its effects can be seen, as Gaines mentions, throughout the twentieth century and into our own. That is a discussion for another day.

To me, the Whitney appears akin to the Holocaust Museum. After you go, you cannot think about things the same way again. It also contains similarities to art and literature. These things bring us close to reality even though they are fabrications of it. They make us empathize and ponder the quandaries that surround us daily. I have written about this topic before, and I urge you to go back and read what I have to say about art's power over an audience.

I want to leave you with a couple of links about Whitney Plantation:

- Interview with Dr. Seck (KRVS)

- "Building the First Slavery Museum in America" (New York Times)

- "New Museum Depicts the Life of a Slave" (NPR)

- "The Whitney Plantation: Looking Back to Look ahead" (NBC12)

If you went to Dr. Seck's lecture or have been to the Whitney Plantation, what are your thoughts? Please share them below.

Thursday, March 5, 2015

Mitchell S. Jackson's "The Residue Years"

I just finished Mitchell S. Jackson's The Residue Years (2013) which won the 2014 Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence. As usual, there is a lot that I could say about this work; however, I just want to focus on one specific scene, and while focusing on that scene, I hope that you get an understanding of Jackson's novel and pick it up for yourself. I would love to hear what you think of it in the comments below.

The Residue Years centers around the Thomas family, specifically the matriarch Grace and her eldest son Shawn (Champ). Grace and Champ narrate each chapter, and they alternate throughout the novel. At its core, The Residue Years explores issues regarding family, race, the American Dream, and poverty. Grace, who used to work a corporate job, has just gotten out of prison at the beginning of the novel and must continually check in with her court appointed social worker to finish her rehab program. Starting off strong, the daily grind that she has to endure to get a job, make it to that job, and just plain survive finally gets to her and she relapses back into her old habits, eventually landing up back in jail and rehab. Champ, on the other hand, is in college, and his professor tries to talk him into going to graduate school. All the while, he sells drugs and works--hard--to try and buy his family's house on Sixth Street (one of the houses he lived in with his mom and brothers when he was younger). Throughout, this is his goal, but a white, middle-class man named Jude cons him out of the money he wants to use for house, and Champ, like his mother, ends up in jail at the end of the novel.

The above does not tell the whole story. While reading, I couldn't help but think about Donald Goines's Dopefiend (1971) or Vern E. Smith's The Jones Men (1974) and their focus on the ravages of drugs and poverty on individuals, but that is a discussion for another day. One of the main conflicts in the novel involves Grace's desire to stop her ex, Ken, from gaining full custody of her two youngest sons KJ and Canaan. The novel concludes with Grace going on a bender only two days before the court date where she must appear to prove that she can raise the boys and see them. Earlier, Grace has Champ get the boys and bring them to her so they can enjoy a day at Multnomah Falls. There is nothing insidious about Grace's plan; she just wants her sons to know that she cares and to create an experience that they can share in support of her when everyone gathers in court.

|

| Multnomah Falls |

In many ways, Grace's assertion reminds me of one of my favorite Langston Hughes poems "Mother to Son," a poem where a mother tells her son that life is not a crystal stair. The smooth, easy path does not exist; rather, "It's had tacks in it, And splinters,/ And boards torn up,/ And places with no carpet on the floor--Bare." All the while, though, the mother tells her to keep going, around dark corners over cracks, even though he feels like he wants to turn around and go back down. Even though it's hard, the mother says, "I'se still climbin'." Like Grace, she continues, no matter the obstacle. Like Grace, she wants a life for her a son, a life that appears better than the one she had. Like Grace, she loves her son and gives his advice on how to navigate a world that keeps him down because of the color of his skin. While trying to maintain her upward assent, Grace falls though, a warning that the mother in Hughes' poem warns her son about. The mother tells her son that even though its dark he must not turn back; he must not start the descent because life gets hard; he must keep climbing.

Jackson's novel traces Grace's attempts to rehabilitate her life and to not fall back into her old ways, but the environment grabs her and refuses to let her escape. The environment ensnares Champ as well, leading him into a life as a drug dealer even though he had (and lost) a D-1 basketball scholarship and decides to apply for graduate school. More could be said, as I point out earlier, but for now, I would like to leave you with one more observation. Thinking about Grace, I also couldn't help but think about characters like Aunt Charlotte and Tante Lou in Gaines's works. Both of these women sacrificed for Jackson and Grant respectively. While the situations of Grace and Gaines's characters differ, they are similar in certain ways. What do you think? If you've read Jackson's The Residue Years, what themes stuck out to you?

Jackson, Mitchell S. The Residue Years. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013. Print.

Tuesday, March 3, 2015

The Importance of Art

Last week, Irvin Mayfield appeared at UL Lafayette as an artist in residence for three days. During that time, he spoke with students in various classes including literature and music classes, he performed with the UL Jazz Combo I and his quintet, and he strengthened my beliefs in the power of the arts and the humanities in society. This post could devolve into a lifelong look at how the arts have affected me throughout my life, but I'm not going to do that. Instead, I'm going to just make a few observations regarding my thoughts about the arts and humanities. He speaks about these ideas in his interview with Judith Meriwether on KRVS.

To begin with, I've always felt that music resides at the pinnacle or artistic expression in regards to its ability to communicate emotion and feeling to not just an audience but to the performer as well. Without knowing the words, if there are any, a composition can move you in certain ways whether that's making you fell joy, sadness, anger, or any other emotion. At the concert last Tuesday and at the world premier of James Syler's Congo Square on Friday night, this belief struck home with me again. The Irvin Mayfield Quintet performed a piece from Dirt, Dust, and Trees entitled "Angola." The piece explores themes of struggle and persecution that appear in Gaines's works. Speaking about the song, Mayfield said that he asked Gaines why all of the heroes in his novels die, and Gaines replied by simply telling him that they must because they cannot live in a world that treats them the way that it does. "Anogola," which takes its name from the infamous Louisiana State Prison, reluctantly moves the listener through the pain and struggles of numerous individuals, mostly African American males, who are incarcerated in this country for no other reason than their class status or color.

I had heard this song once before at the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence ceremony; however, last week the piece carried a heavier weight for me, not because of anything different since the first time I heard it performed a month earlier, but because of the sounds that evening. It opens with just the drum for a few measures then the piano and bass enter creating an ominous, almost desperate feel. Sitting in Angelle Hall, the Jamison Ross started the song, and all I could notice was that when he hit the bass drum, the snare drum, and the hi hat the sound left the stage, traveled to the back of the auditorium, then returned, albeit a little quieter. At that moment, my mind shifted to Marcus standing before Bonbon's horse in the fields, to Jefferson, feeling like a hog, in the jail cell in Bayonne, to Charles Blow's son being accosted by police at Yale, to mothers and fathers having to tell their sons to keep their hands on the wheel when being pulled over just because of the color of their skin, to rappers being pulled over by police-again because of their skin. The list could go on, and on, and on, and on. Once Max Moran's walking bass line and Joe Ashlar's piano introduced themselves, I began to drift, and get lost, not even recalling much of the song until Irvin and trombonist Michael Watson blared on their horns and brought me out of my thoughts back to that jail cell in Bayonne, a fictional jail cell, where Jefferson anguishes about what has happened and what will eventually happen to him. Jefferson screams in that cell, wanting to be recognized as a man, a person, a human being with thoughts and ideas. He gets that recognition, from Grant, from Paul, and from others, but not until he sits in Gruesome Gertie and perishes. That is what the sounds coming from the stage that night did for me. That is what they said to me at that moment.

On Monday, Mayfield spoke with an English class about art and its importance. Constructing the class around a conversation, he asked the students to help him define words such as "idea" and "event." As the class progressed, other words appeared and entered the conversation. At one point, the discussion moved towards what constitutes creativity and art; here, the question of whether or not the building the students were sitting in should be considered a form of creative expression. Some students looked puzzled, and others agreed that it should. As the conversation moved towards the planning of cities and neighborhoods, then to the French Quarter and its history, I thought about what architecture says about the society, and specifically I thought about the Louisiana State Capital. I've written about the capital on this blog before, but what I did not mention is the fact that the capital contains numerous carvings relating to Louisiana history. One aspect of that history that does not appear is slavery. There are images of settlers interactions with Native Americans and of what appear to be slaves, but could be share croppers, in the fields. However, there are no images of slave auctions, scourging, of other aspects. History contains the good and the bad, and shouldn't both be exposed lest we forget where we came from?

Continuing my thoughts about the capital, I had an opportunity to speak with Mayfield at a reception and he started discussing how corporations and the government use art to control. That's why we don't have those images in the state capital. Think about at MLB, NBA, and NFL games. What does art have to do with these events? At each one, every night, someone performs "The Star Spangled Banner." Why? The singing of our national anthem began in earnest in sports in the seventh inning of the first game of the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs. Why is this important? It's important because America, 17 months earlier, entered World War I. The anthem became a patriotic rallying cry, as we saw after September 11. Once the owners realized that people responded to the song, they began to have it performed again and again. I'm not saying that the anthem is a bad thing; I am only saying that we need to think about how art and artistic expression relate to events that we may not even consider them being a part of and what that incorporation means. The NFL started to get bigger after a couple of specials on NBC that had artistic merit and led to the creation of NFL films. It brought the game closer to the fans by making it personal and artistic.

With all of that said, I want to leave you with a couple of parting thoughts and questions. What teachers do you remember from your educational career? For me, it's the English teachers. Granted I'm in English, but those are the teachers I remember the most. It can't be a coincidence that others, who do other things, remember them as well. Liberal arts matter. College should, as Frank Bruni says in "College's Priceless Value: Higher Education, liberal Arts and Shakespeare," work to make us better citizens. Literature, and all art, opens our eyes to those around us, that we may see, but more often than not, that we don't see. It relates the human condition to us, and as I have had students tell me, in Bruni's words, "It informed all my reading from then on.

Part of studying literature, art, history, music, etc, is to learn how to see through the noise and make up your own mind about issues and ideas instead of listening to the same old rhetorical bombast and idiocy that spews from the mouths of those that want to either hold on to their power or to grab a piece for themselves. It forces you, sometimes reluctantly, to take the red pill, opening you up to realities that either eluded you or you ignored. Your stomach will wrench, your eyes will cry, your mouth will laugh, and your ears will hear. Most importantly, your heart will expand by studying the liberal arts.

As I am fond of quoting James Baldwin on this topic, "You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive."

To begin with, I've always felt that music resides at the pinnacle or artistic expression in regards to its ability to communicate emotion and feeling to not just an audience but to the performer as well. Without knowing the words, if there are any, a composition can move you in certain ways whether that's making you fell joy, sadness, anger, or any other emotion. At the concert last Tuesday and at the world premier of James Syler's Congo Square on Friday night, this belief struck home with me again. The Irvin Mayfield Quintet performed a piece from Dirt, Dust, and Trees entitled "Angola." The piece explores themes of struggle and persecution that appear in Gaines's works. Speaking about the song, Mayfield said that he asked Gaines why all of the heroes in his novels die, and Gaines replied by simply telling him that they must because they cannot live in a world that treats them the way that it does. "Anogola," which takes its name from the infamous Louisiana State Prison, reluctantly moves the listener through the pain and struggles of numerous individuals, mostly African American males, who are incarcerated in this country for no other reason than their class status or color.

I had heard this song once before at the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence ceremony; however, last week the piece carried a heavier weight for me, not because of anything different since the first time I heard it performed a month earlier, but because of the sounds that evening. It opens with just the drum for a few measures then the piano and bass enter creating an ominous, almost desperate feel. Sitting in Angelle Hall, the Jamison Ross started the song, and all I could notice was that when he hit the bass drum, the snare drum, and the hi hat the sound left the stage, traveled to the back of the auditorium, then returned, albeit a little quieter. At that moment, my mind shifted to Marcus standing before Bonbon's horse in the fields, to Jefferson, feeling like a hog, in the jail cell in Bayonne, to Charles Blow's son being accosted by police at Yale, to mothers and fathers having to tell their sons to keep their hands on the wheel when being pulled over just because of the color of their skin, to rappers being pulled over by police-again because of their skin. The list could go on, and on, and on, and on. Once Max Moran's walking bass line and Joe Ashlar's piano introduced themselves, I began to drift, and get lost, not even recalling much of the song until Irvin and trombonist Michael Watson blared on their horns and brought me out of my thoughts back to that jail cell in Bayonne, a fictional jail cell, where Jefferson anguishes about what has happened and what will eventually happen to him. Jefferson screams in that cell, wanting to be recognized as a man, a person, a human being with thoughts and ideas. He gets that recognition, from Grant, from Paul, and from others, but not until he sits in Gruesome Gertie and perishes. That is what the sounds coming from the stage that night did for me. That is what they said to me at that moment.

On Monday, Mayfield spoke with an English class about art and its importance. Constructing the class around a conversation, he asked the students to help him define words such as "idea" and "event." As the class progressed, other words appeared and entered the conversation. At one point, the discussion moved towards what constitutes creativity and art; here, the question of whether or not the building the students were sitting in should be considered a form of creative expression. Some students looked puzzled, and others agreed that it should. As the conversation moved towards the planning of cities and neighborhoods, then to the French Quarter and its history, I thought about what architecture says about the society, and specifically I thought about the Louisiana State Capital. I've written about the capital on this blog before, but what I did not mention is the fact that the capital contains numerous carvings relating to Louisiana history. One aspect of that history that does not appear is slavery. There are images of settlers interactions with Native Americans and of what appear to be slaves, but could be share croppers, in the fields. However, there are no images of slave auctions, scourging, of other aspects. History contains the good and the bad, and shouldn't both be exposed lest we forget where we came from?

Continuing my thoughts about the capital, I had an opportunity to speak with Mayfield at a reception and he started discussing how corporations and the government use art to control. That's why we don't have those images in the state capital. Think about at MLB, NBA, and NFL games. What does art have to do with these events? At each one, every night, someone performs "The Star Spangled Banner." Why? The singing of our national anthem began in earnest in sports in the seventh inning of the first game of the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the Chicago Cubs. Why is this important? It's important because America, 17 months earlier, entered World War I. The anthem became a patriotic rallying cry, as we saw after September 11. Once the owners realized that people responded to the song, they began to have it performed again and again. I'm not saying that the anthem is a bad thing; I am only saying that we need to think about how art and artistic expression relate to events that we may not even consider them being a part of and what that incorporation means. The NFL started to get bigger after a couple of specials on NBC that had artistic merit and led to the creation of NFL films. It brought the game closer to the fans by making it personal and artistic.

With all of that said, I want to leave you with a couple of parting thoughts and questions. What teachers do you remember from your educational career? For me, it's the English teachers. Granted I'm in English, but those are the teachers I remember the most. It can't be a coincidence that others, who do other things, remember them as well. Liberal arts matter. College should, as Frank Bruni says in "College's Priceless Value: Higher Education, liberal Arts and Shakespeare," work to make us better citizens. Literature, and all art, opens our eyes to those around us, that we may see, but more often than not, that we don't see. It relates the human condition to us, and as I have had students tell me, in Bruni's words, "It informed all my reading from then on.

Part of studying literature, art, history, music, etc, is to learn how to see through the noise and make up your own mind about issues and ideas instead of listening to the same old rhetorical bombast and idiocy that spews from the mouths of those that want to either hold on to their power or to grab a piece for themselves. It forces you, sometimes reluctantly, to take the red pill, opening you up to realities that either eluded you or you ignored. Your stomach will wrench, your eyes will cry, your mouth will laugh, and your ears will hear. Most importantly, your heart will expand by studying the liberal arts.

As I am fond of quoting James Baldwin on this topic, "You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, or who had ever been alive."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)