|

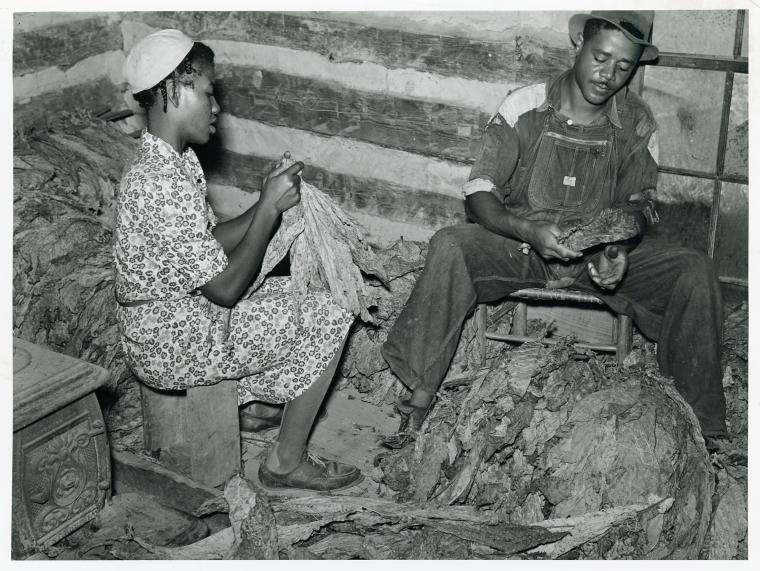

| African American sharecropper and wife grading tobacco in North Carolina (New York Public Library) |

"Requiem for Tobacco" begins nostalgically, almost like a myth that was once true but as of now no longer exists.

You remember, though perhaps you don't, that once upon a time men harvested tobacco by hand. There was a time when folk were bound together in a community, as one, and helped one person this day and that day another, and another the next, to see that everyone got his tobacco crop in the barn each week, and that it was fired and cured and taken to a packhouse to be graded and eventually sent to market. But this was once upon a time. (254)"Once upon a time," as Davis notes, carries with it a note of mythologizing the harvest. The phrase, in one form or another, appears twice in the paragraph above, once at the beginning and once at the end. Along with this phrase, there is also a focus on community. Looking to the past, the narrator points out that it "was a time when folk were bound together in community." Community plays a major role in Gaines's work, and in Kenan's novel, the community that "Requiem for Tobacco" recalls does not exist anymore. Instead, the community does not help one another out; in fact, it hinders the psychological growth of the presumed One, Horace.

After speaking about the planting, harvesting, and drying of the tobacco. Men like Edgar Harris and George Pickett would plant and harvest the tobacco then bring it to the barn where the women would tie the tobacco together. Underneath the tin ceiling, time would fade away, problems would be solved, and the older women would "impart good and practical wisdom to younger girls" (256). All of this though, happened in the past. Over time, the land, and who cultivated it, changed. The encroachment of modernity upon the rural North Carolina community recalls the continued approach of mechanized farming in Catherine Carmier and A Gathering of Old Men. Now, Edgar Harris lies in a grave somewhere and "George Pickett has leased his land and now drives a bus" (256). Pickett's land then became divided again, sold to someone who had a lot of land, "someone who is no one at all, but many in the name of one," a corporation like the one that harvests sugarcane in Attica Locke's The Cutting Season (256). Instead of hands doing the work, "the clacking metal and durable rubber of a harvester that needs no men, that picks the leaves, stores the leaves, slaps them into small bulk barns that looks like chicken coops that cure quicker, easier, cheaper" replaced the people in the fields (256-57). The increase in mechanized farming and corporations concerned more with profit margins than with people push the memories of Hiram Crum, Ada Mae Philips, Jess Stokes, Henry Perry, and Lena Wilson to the side, letting them drift in the wind like the dust kicked up by a laboring tractor.

"Requiem for Tobacco," and the novel, concludes with paragraph that laments the passing of time. Even though machines make farming "less torturous," they also erased the past. With the movement of modernity, the past becomes forgotten, only to be recalled when modernity causes us to feel more disoriented then ever from trying to keep up. That is when we turn to the rural, the pastoral, for an escape from the overwhelming onslaught. That should not be the only time. As the narrator concludes, "And it is good to remember that people were bound to" the process of growing tobacco "for too many forget" (257). This is what Gaines writes for. This is what Kenan's A Visitation of Spirits does. They cause us to remember, to look at the past and to recall how we made it to the present.

|

| Wood Plank Road in Fayettville, NC (1984) |

What other instances in Kenan's novel highlight the changing times? Are there other instances that remind you of Gaines or other Southern authors? If so, what are they?

Davis, Thadious M. Southscapes: Geographies of Race, Region, & Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Print.

Kenan, Randall. A Visitation of Spirits. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment