|

| Donald Goines |

About a month ago I wrote a post entitled "The Short Story and Ernest Gaines Syllabus." Today, I would like to do something similar. However, instead of having the syllabus center around Gaines and his relation to the short story genre, I want to share with you a syllabus I constructed entitled "African American Crime and Detective Fiction." The syllabus below does not contain an exhaustive list of texts that could be included in this course. With that said, in the comments below, tell me what suggestions do you have for texts, critical or otherwise, that could be added to this course.

African American Crime and Detective Fiction

Course Description:

This

course will cover African American crime and detective novels of the twentieth

and twenty-first centuries. Beginning with the Harlem Renaissance, we will

trace a path from Rudolph Fisher to more recent authors such as Walter Mosley

and Attica Locke. Primarily focusing on the urban landscape, we will examine

how these authors navigate the constricted spaces of the urban environment and

how they work to control that environment through various means. As Otto

Penzler states in the introduction to Black

Noir: Mystery, Crime, and Suspense Fiction by African American Writers,

African American crime literature shows “the detective in a reasonably insular

community, trying to solve crimes with black victims and committed, in all

likelihood, by black villains.” This course will provide students with the opportunity

to explore Penzler’s assertion and to see how that statement has either changed

or remained the same throughout the years.

Beginning with Fisher, the course will trace the proliferation of

African American crime and detective literature that saw an upsurge in the

1960s and 1970s through the first part of the twenty-first century.

Readings:

- Rudolph Fisher The Conjure Man Dies (1932)

- Chester Himes

Cotton Comes to Harlem (1965)

- Iceberg Slim

Trick Baby (1967)

- Donald Goines Dopefiend (1971)

- Ishmael Reed Mumbo Jumbo (1972)

- Vern E. Smith The Jones Men (1975)

- Roland S. Jefferson The School on 103rd Street (1976)

- Ernest J. Gaines A Gathering of Old Men (1983)

- Walter Mosley

Devil in a Blue Dress (1990)

- Sista Souljah

The Coldest Winter Ever (1999)

- Percivel Everret Erasure (2001)

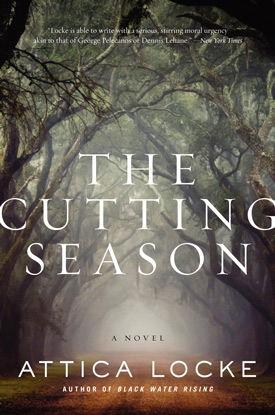

- Attica Locke The Cutting Season (2011)

Secondary Texts:

- Stephen F. Saitos The Blues Detective: A Study of African American Detective Fiction

(1996)

- Black Noir: Mystery, Crime, and Suspense Fiction by African American Writers.

ed. Otto Penzler (2009)

- Justin Gifford Pimping Fictions: African American Literature and the Untold Story of Black Pulp Publishing (2013)

Assignments:

- Response papers: These will be in the form of blog posts. I will set up a blog for the class, and you will post your responses there. Each post will require you to provide an answer to my prompt and to respond to other students' responses as well. We will discuss how to do this in a proefssional manner during class. (Teachers, see Shannon Baldino's "The Classroom Blog: Enhancing Critical Thinking, Substantive Discussion, and Appropriate Online Interaction" for a discussion of blogs in the high school classroom.)

- Wiki: Students will be placed into groups of four. Each group will be required to construct a collaborative wiki with ________ components on an author and text that we read in class.

- Each student must write a paragraph describing the class discussion for that author. For example, if the class discusses narrative voice in Donald Goines, the response should talk about narrative voice and what the class said about it.

- The group must come up with five questions to think about based off of the class discussion or research.

- The group must construct an annotated bibliography of six sources. The annotations must be 250-500 words and contain a section stating the source's credibility, a summary of the source, a way to use that source in a research project.

- The group must construct a list of symbols/allusions/or other references in the stories. The number here will vary, but each entry must provide information about where it comes from (especially for an allusion) and what purpose it serves in the context of the story.

- The group must construct a review of the short story. The review must be between 500-1000 words. Remember, a review is not a summary. Some summary is necessary, but the thrust of the review should be about the story's meaning and importance.

- The group must construct a creative page. This page can be anything that you desire. For example, it could be a hand drawn map of the setting. It could be sketch of one of the scenes. It could be a Prezi talking about the author and the themes of the story. It could be a video discussion. This page is open to whatever you want to do.

As stated at the beginning of this post, the readings above are not an exhaustive list of texts that could be used for this class. The ones that I chose provide an overview of African American crime and detective fiction drawing from both canonical and popular texts. I chose to do this because, as Justin Gifford says, "If we are truly invested in American and African American literary traditions and their larger relationships to cultural politics, popular movements, and social change, then black crime fiction presents us with a unique opportunity to redraw the very boundaries of what counts as the American canon and even cultural knowledge" (7). Considering canon formation, providing students with a wide swath of texts will give them insight, and allow them to challenge, the idea of canon formation in literature. Essentially, students could ask whether or not texts buy authors such as Goines, Jefferson, and Slim should be included alongside those by Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison, and James Baldwin.

Along with questioning canon formation, two of the texts above (Gaines and Locke) do not center on the urban environment. What do texts like these do to the assumption that crime and detective novels typically take place in urban settings? How does the rural setting disrupt that assumption? With this in mind, I could have added Goines' Swamp Man to the list above. What other African American crime and detective novels take place outside of the urban environment? Could there be an entire course focused on that strand of crime and detective fiction?

List of previous blog posts that may be of help with the readings in this course:

- Pulp Novels and Ernest Gaines?

- Attica Locke's "The Cutting Season"

- "No, I won't let them harm my people."

- Chandler's "The Big Sleep" and the Issue of Class

- In the Background of Chandler's "The Big Sleep"