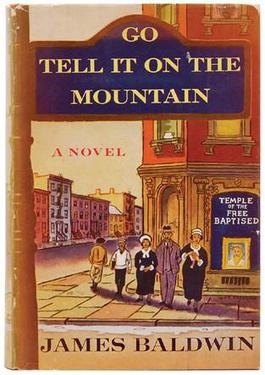

Writing about James Baldwin's, Charles Scruggs notes that "[n]o Afro-American writer in modern literature conveys better the sense of menace lying in wait in the urban streets 'outside.' Word such as 'menacing,' 'dreadful,' and 'unspeakable' are Baldwin's choices for describing those streets" (147). Later, Scruggs points out that for Baldwin "[s]mall, intimate spaces" take the place of "sacred space" within the city (147). This is where I would like to spend today's post, on Baldwin's description of those "small, intimate spaces," specifically the apartment of the Grimes family in Go Tell It On The Mountain.

As he wakes out of a bleary sleep on his birthday in 1935, John thinks about whether or not anyone will remember his birthday as he stares at "a yellow stain on the ceiling just above his head" that eventually transforms "into a woman's nakedness" (18). The stain becomes something that causes John to sin, making him feel guilty. The dinginess of the stain makes one think of Bigger Thomas's apartment in Native Son or of Gwendolyn Brooks's poem "Kitchenette Building." For me, the narrator's later descriptions of the apartment and the suffocating dirt that inhabits it. The use of "dirt" reminds me, of course, of Gaines's implementation of "dust" and "dirt" as an oppressive and stifling force in Of Love and Dust. In Baldwin's novel, "dirt" appears in the same way; however, instead of being outside in the fields, the "dirt" becomes a presences within the confines of the small apartment.

John must clean the constricting apartment, dusting and sweeping its interior. The cramped apartment served as a breeding ground for roaches, and it could never become clean. "Dirt was in the walls and floorboards," the narrator says (21). When John begins cleaning, he discovers that no matter how hard he tries, the apartment will never be rid of the "dirt."

Dirt was in every corner, angle, crevice of the monstrous stove, and lived behind it in delirious communion with the corrupted wall. Dirt was in the baseboard that John scrubbed every Saturday, and roughened the cupboard shelves that held the cracked and gleaming dishes. Under this dark weight the walls leaned, under it the ceiling, with a great crack like lightening in its center, sagged. The windows gleamed like beaten gold and silver, but now John saw, in the yellow light, how fine dust veiled their doubtful glory. Dirt crawled in the gray mop hung out of the windows to dry. John thought with shame and horror, yet in angry hardness of heart: He who is filthy, let him be filthy still. (22)Within this section of a paragraph, "dirt" and "dust" appear four times. "Dirt" occupies the space, causing it to become a disheveled, oppressive space that does not even allow the light from outside to penetrate its darkness. Maintaining its constriction on the apartment, the "dirt" even takes on animalistic characteristics. It "crawled" into the mop and "veiled" the beauty of the light. These words connote something sinister that the "dirt" represents.

Later, the cleaning of the apartment becomes akin to Sisyphus continually rolling the boulder up the hill only to have it pushed back down for all eternity. Sweeping the carpet, "dust rose, clogging [John's] nose and sticking to his sweaty skin, and he felt that should he sweep it forever, the clouds of dust would not diminish, the rug would not be clean" (26). No matter how much John swept and cleaned the rug or the apartment, the dust remained, clogging every crevice and creeping into the implements whose sole purpose was the clean the apartment.

Scruggs views John's cleaning of the apartment as "a metaphor for Gabriel's morally untidy life, and John's pointless labor illustrates the circles of deception and self-deception which surround the father's authority" (151). I agree with Scruggs on this point, but I also see the "dirt" as a physical contagion that entraps not just John and his family but an entire community in a space of subjugation and oppression. It clogs their pours, in much the same way that the "dust" in Gaines's novel swirls, blisteringly around the characters causing them to seek shelter. Unlike Gaines's characters, the Grimeses cannot go inside to escape the "dust"; when they retreat inside, they encounter the "dirt" all around them.

More can, and should be said about this. What are your thoughts? If you recall, during John's passing through at the end of the novel, he feels like his mouth is filled with "dirt" and he can't breathe. What role does "dirt" play in this instance? What are some other places within Go Tell It On the Mountain or other Baldwin texts where "dirt" or other elements work as symbols of oppression?

Baldwin, James. Go Tell it On the Mountain. New York: Dell, 1985.

Scruggs, Charles. Sweet Home: Invisible Cities in the Afro-American Novel. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1993. Print.