From my gallery I could see that dust coming down the quarter, coming fast, and I thought to myself, "Who in the world would be driving like that?" I got up to go inside until the dust had all settled. But I had just stepped inside the room when I heard the truck stopping there before the gate. I didn't turn around then because I knew the dust was flying all over the place. A minute or so later, when I figured it had settled, I went back. The dust was still flying across the yard, but it wasn't nearly as thick now. I looked toward the road and I saw somebody coming in the gate. It was too dark to tell if he was white or colored. (3)The word "dust" appears in four of the eight sentences in the opening paragraph of the novel. Granted the word shows up in the title, but four mentions in the first 128 words warrants attention. What does the repetition of this one word mean?

In "Of Snow and Dust," Matthew Spangler speaks about James Joyce's presence in Gaines A Lesson before Dying, something I have mentioned on this blog before. Discussing how "soot," "smoke," "dust", and other elements work to show a character's attitude towards his or her setting, Spangler addresses the opening paragraph. For Spangler, "Gaines's us of dust draws upon American cultural narratives of the wild, rural, pre-settled nation, particularly those associated with the American West and South" (112). Spangler claims Gaines's use of "dust" becomes "a symbol for paralysis and entrapment" (113). With this assertion, I wholeheartedly agree. In the novel,"dust" becomes synonymous with heat, sweat, work, grime, and oppression.

As James walks back down the quarter, he begins to think about the oppressive heat: "It must have been a good hundred. That dust was white as snow, hot as fire. The sun was straight up, so it didn't throw any kind of shadows across the road. You had nothing but hot dust to walk in from the time you left the highway until you got home" (82). The reflection of the sun off of the dust is white enough to blind him, and the heat is so unbearable that when he gets home he will have a hard time being able to relax, as he mentions earlier that he couldn't fall asleep on his bed because of the heat. The dust symbolically smothers and blinds the characters in the same way that the oppressive system that they live within does. The novel is full of characters "sweating," "squinting eyes because of reflections," "dirt caked faces," and "oppressive heat." It would take too long to mention them all.

To conclude, I want to quote a brief passage from the end of the novel. Here, James is relating Sun Brown's account of Marcus's death at the hands of Bonbon. James says, "Then [Sun Brown] saw a car coming toward him--no, he saw the dust. The dust was flying all over the quarter. In front of the dust was a car, coming up the quarter with no lights on" (274). Sun Brown's account of Bonbon's car speeding through the quarters mirrors James's at the beginning. Before he sees the car, sun Brown sees the dust, flying all of the place; then, he sees the car in front of it. Unlike the opening paragraph, there is not mention of the dust clearing. Here, at the climax of the novel, the dust overcomes Marcus. He cannot escape the rules of the plantation and the Deep South by heading North with Louise. Instead, the suspended dust metaphorically suffocates him while Bonbon literally kills him with a farming implement (a scythe).

Next post I plan to talk about manhood in the novel. What are some other instances in the novel that show the landscape as a symbol of the subjugation in the novel? Are there other instances? What other works, like Joyce and Gaines, use landscape as this type of symbol? Let me know in the comments below.

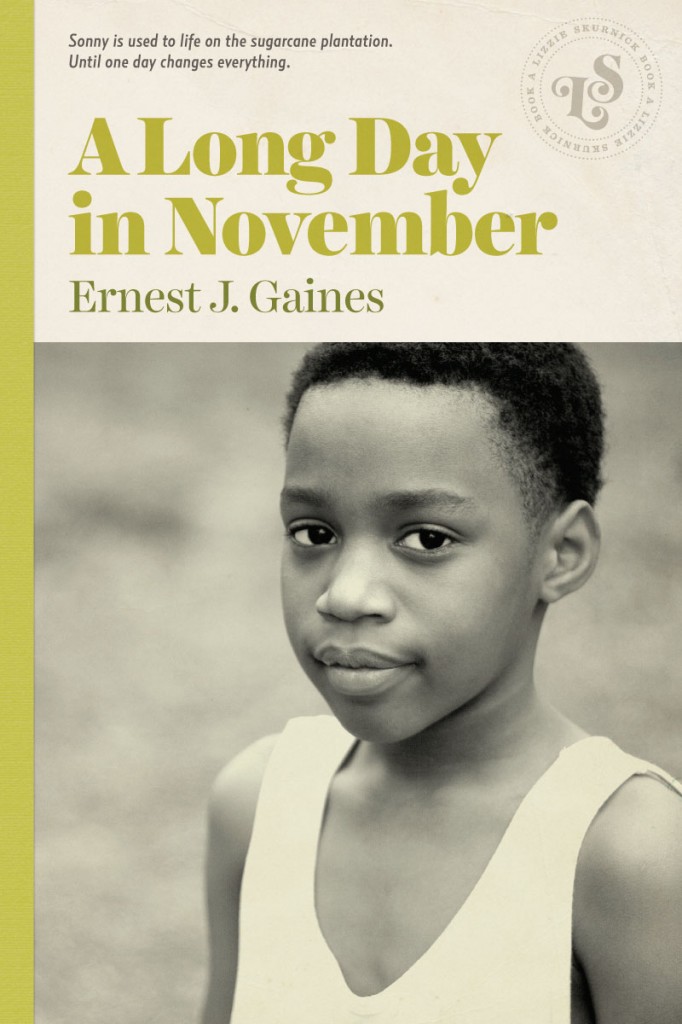

Gaines, Ernest J. Of Love and Dust. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1979. Print.

Spangler, Matthew. “Of Snow and Dust: The Presence of James Joyce in Ernest Gaines’s ‘A Lesson Before Dying.’” South Atlantic Review 67:1, 2002. 104-128. Print.