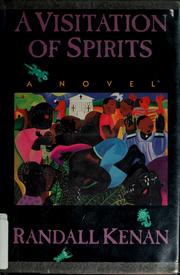

On the surface, Randall Kenan's A Visitation of Spirits (1989) may not seem similar to works by Ernest J. Gaines, at least in regards to the writing style. Kenan's novel oscillates from narrative to narrative in a postmodernist stream-of-consciousness flow. Gaines, on the other hand, writes in a more straight forward narrative style that mirrors Hemingway, with the occasional stream-of-consciousness here and there. While styles do not necessarily link Gaines and Kenan, other similarities do arise here and there. What one sees when reading Gaines and Kenan in unison arises from the thematic similarities of two African American men from the South but born thirty years apart. Even though he was born in New York, Kenan grew up in North Carolina, and Chinquapin, NC, serves as the inspiration for Tims Creek, the community where Kenan sets his fiction. Along with the creation of specific space like Gaines's Bayonne and Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County, he allows for a sense of reality in his fiction, even though the novel is very speculative, filled with demons and other spirits that occupy the mind of Horace Cross.

While reading, there are certain aspects of A Visitation of Spirits that make me think of Gaines and Southern writers. For one, I think about community. Gaines's works center on community, as I have noted before. The community in the quarters, to a certain extent, serves as a space where the African American occupants do not come face-to-face with racism and oppression as they do when they go to town. Think about Gaines's "The Sky is Gray" here. James does not experience overt subjugation in the quarters; he experiences community. When he goes to Bayonne, he starts to come more overtly into contact with the systems that keep him oppressed. In Gaines's work, the community struggles with the legacy of slavery, but they all form a system that supports and works together. However, as Trudier Harris argues, "the legacies of slavery are somewhat in the background" of Kenan's novel, and "a sense of black family tradition has become so all-consuming that it is perhaps worse than slavery" (115). At the center of this "all-consuming" community is Horace Cross, "the Chosen Nigger" (13). Harris points out that Horace's being labeled "the One" that will serve as a leader for the community mirrors numerous characters in Gaines's works, most specifically Ned Douglass and Jimmy Aaron in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971).

While Ned and Jimmy both succeed in becoming "the one," Horace Cross cannot. He studies, maintains good grades, and works hard to become something extraordinary beyond the teachers, preachers, and lawyers that surround him. However, Horace is gay, and the patriarchal, heterosexual family lineage that values the conquering of "pussy" does not allow for a homosexual leader (55). Instead of being lifted up and groomed to be the leader of the people, the community diminishes Horace's worth and condemns him vociferously. In the church at night, Horace envisions the pastor condemning him from the pulpit and calling him calling him "unclean." Then, Horace starts to hear voices from the congregation, including his family. They say,

Wicked. Wicked.

Abomination.

Man lover!

Child molester!

Sissy!

Greyboy!

Old men, little girls, widows and workers, he saw no faces, knew no names, but the voices, the voices . . .

Unclean bastard!Through their name calling and other actions, the community that initially labels Horace as "the One" systematically tears him down, refusing to accept him as he is and leading him to his ultimate demise. In Kenan's novel, the downfall of "the One" does not come from the outside community, the white community that tries to maintain its rule over the African American community. Instead, the destruction occurs from the inside. This is not to say that the residual effects of slavery do not contribute to the people "othering" Horace. I would even argue that the labeling of Horace as "the Chosen Nigger" works to devalue his place as well. Instead of calling him "the chosen One," the epithet used completely reduces Horace to a person who will not become a savior for those around him but to someone who will go through life subjugated and beaten down by a system that continually strives to maintain control.

Be ashamed of yourself!

Filthy knob polisher! (86-87)

In the next post, I will talk about another similarity I see between Gaines and Kenan: the land. Both authors describe the land thoroughly, and its changing appearance. What similarities do you see between the two authors? Let me know in the comments below.

Harris, Trudier. The Scary Mason-Dixon Line: African American Writers and the South. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2009. Print.

Kenan, Randall. A Visitation of Spirits. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment